The city sounds different these days. I live on a relatively

quiet block of a narrow street connecting busy Connecticut and Massachusetts

Avenues. As I write this morning, I hear rain falling, birds chirping, a car

engine belching. Sometimes I hear the beep beep beep of a truck backing up, the

slamming of the back of a delivery truck, dogs barking, snippets of

conversation, helicopters. Some are natural others machine sounds, the mix tape

of the random noises of urban life. But it's definitely quieter than Before. Silence in the city can be a precious

commodity—and it is a commodity

commanding a high price—but a silent city is also unnerving. Like Rachel Carson’s

warning about a pesticide-induced “silent spring,” silent streets and sidewalks

are an ominous sign.

Over the last year a string of restaurants on Connecticut

Avenue just north of Dupont Circle had begun to host regular live music. The

old Childe Harold—I know it has another name, but it will always be Childe

Harold to me—had gotten back to its live music roots; several newer places had

begun to feature a single guitar player or small combo, often set up in the

front window. Music leaked out onto the sidewalk, mixing with the noise of cars

and horns and conversations. This was my evening soundtrack as I walked home

from Metro in the Before Times. Now, just silence.

| |

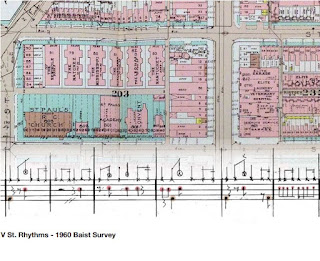

| Zach Moshier,Urban Rhythms of Washington DC, Masters thesis, 2016 |

What does a healthy street sound like? And what is its antiphonal call and response—what is it saying, and what do we hear? The

medical analogy does apply but since I’m not a doctor (nor do I play one on TV)

I prefer to think of another type of listening—not to the noise of a body, but to music. When

Mattern used the phrase “scoring the city,” I thought of the thesis

of a former student, who was also a drummer in the WAAC Band. Zach really did

score the city: he looked at historical maps to see—and hear—how the beat of V Street had changed over the years. It was a

revelation: sound, not only sight, can be an instrument of urban analysis and

design.

“Just listen to the music of the traffic in the city,”

Petula Clark sang in her urban love song, Downtown.

I’ve been writing my own ode to the city during this Covid-hibernation. Called “The City

is Waiting” it's a melancholy reflection on the situation that seemed more suited to music than prose. The refrain is about how the city is listening, waiting, restless, for us to return. When I looked up the lyrics to Downtown to make sure I got Petula’s words

right I was struck by the last line of the chorus: “No finer place, for sure. Downtown. Everything’s waiting

for you.”

No comments:

Post a Comment